mission: impossible, or the assassination of jim phelps by the coward tom cruise

in which tom hijacks a tv show and kills its hero

These days, television and film have never been closer together as media. On one end, huge cinematic universes like the MCU have embraced the kind of longform serialised storytelling once reserved just for TV (note here: one of those comic book movie bros on Twitter proclaiming Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania to be “episode 1 of a huge story”).

On the other, you literally can’t move for TV showrunners proudly marketing their seasons of television as “eight hour movies”, a concept I find heinous, but continues to persist, much like the presence of mould in an excessive amount of London housing. TV has helped blow up cinema’s spot for mid-budget thrillers, which pretty much only exist on HBO et al, and now it’s moved in on mega-budget spectacle: they made The Rings of Power for fucking $45 million an episode.

Adaptations from one to the other, these days, are mostly film-to-TV. On the prestigey end, you have Fargo or Westworld, and on the junkier end you have broadcast TV’s cottage industry of cheap procedural adaptations you’ve probably never heard of, from Lethal Weapon to Minority Report to Training Day to The Exorcist.

Fun fact: they made a pilot for a Fargo procedural in the 90s in which some actors reprised their roles but where Frances McDormand was recast with Edie Falco. I just think trivia is so fun.

These days, with the TV-acting taboo firmly broken for even the biggest stars (did you know that Harrison Ford is a series regular on two streaming shows right now?), a middle way has cropped up, in which sequels or spin-offs to films are now TV shows for streamers desperate for recognisable IP. The Marvel and Star Wars shows fit this bill, but you also have odder examples, like Willow, or The Mighty Ducks: Game Changers, or the Fatal Attraction show for Paramount+ that they’ve already filmed.

Also, The Santa Clauses starring Tim Allen. This family sleighs.

How are they all doing the Dreamworks face?

It’s already been renewed for season two, before you ask. It’s… how do I say it? Still… still Kringle and ready to jingle?

Tim Allen. Booked and busy, folks.

Back in the day, though, film and TV were like church and state, and like many societies, church wielded outsize power. Big films would rarely sink to the level of TV. Instead, some hallowed shows were invited to the big game if they were nice, and made into movies. The ur-example is obviously Star Trek, where both the original and Next Generation casts starred in a total of ten movies, but the likes of The X-Files, M*A*S*H, The Simpsons and of course SpongeBob SquarePants got in on it too. Nothing glitzier than the big screen, folks.

I’m not laying out this potted history in service of explaining The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie or The Simpsons Movie, even though I could if I wanted to, because both films were absolutely vital aspects of my childhood and I could recall to you the Goofy Goober Song or the exact way Homer Simpson says “Alaska” with perfect crystalline clarity. No.

What I mean to say is that Mission: Impossible, the 1996 franchise-starting blockbuster, was one of those lucky shows that dreamed hard and became a movie. But not in a normal way, like all the above examples and more, where either the original cast returned or the familiar characters were at least recast.

No. Tom Cruise wouldn’t make something normal like that.

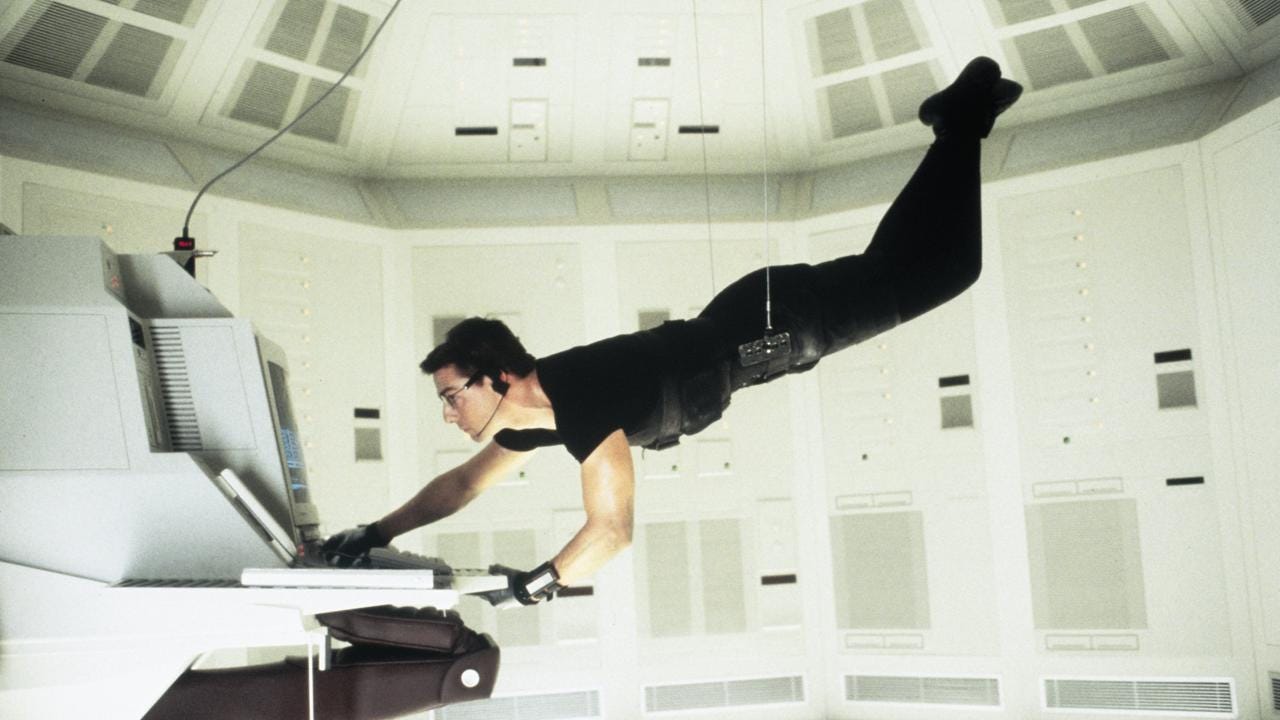

Welcome to Mission: Impossible. Light the fuse!

Mission: Impossible was actually two series in the same continuity - the first ran for seven seasons between 1966 and 1973, and the second ran for two seasons between 1988 and 1990. Both series shared a basic procedural formula, where the “Impossible Missions Force” (get used to that one) solve an impossible mission per episode. More importantly, they shared a main character - team leader Jim Phelps, played by Peter Graves. Phelps was the franchise guy, the Michael Jordan. He’s the leading man. You’d assume.

This is where Cruise comes in again. It’s 1996, ten years after Top Gun. The Cold War is over and Bill Clinton is President. Deep into his blockbuster career now, Cruise is still a red-hot movie star. He’s logged more hit roles in movies like Rain Man, A Few Good Men and Interview With The Vampire, and in the same year as Mission: Impossible, he’ll star in sports film Jerry Maguire, which’ll earn him his first Oscar nomination.

As Cruise’s acting work flourished, he made a decision that’d define the rest of his career: he decided he wanted to help make his big movies, too. In 1992, he set up Cruise/Wagner Productions with his agent Paula Wagner, which would produce some of his biggest movies for the next fifteen years alongside a smattering of other works not starring him.

(I was personally jumpscared recently by his credit on Shattered Glass, the great 2003 journalism drama starring Hayden Christensen in a legitimately great leading role. There’s your six degrees of Kevin Bacon for Cruise and Star Wars.)

There’s nothing exceptionally strange about a big star setting up a production company - the likes of Margot Robbie and Brad Pitt have them these days. With Cruise, though, it’s always helpful to look a little deeper.

Tom Cruise is a control freak. It’s one of his defining attributes. Just about every role he would pick from here on out would be to cultivate a very particular image of himself. For a period of time in the 2000s, when uncomfortable attention was resting on his public persona, it’d become very obvious that Cruise was using his roles to actively push back on how people saw him (we have a lot to talk about with Mission III). This control is necessary. It’s how he survives. Naturally, just being the star wasn’t enough for him.

Production helped him get into all aspects of the creative process, to shape his star vehicles from top to bottom, to make sure it was all part of the ongoing Cruise Project. Cruise was still collaborating with top auteurs - three years after this, he’d knock two of the biggest working directors out in a year - but these projects would gradually dry up as his producer era solidified, and he was pretty much done with all that by the mid-2000s. Not coincidentally, this pretty much lined up exactly with the end of his appearances in supporting roles. On a Tom Cruise project, he’s the star, or he’s not in it at all.

Naturally, then, you’d have to conclude two things from a Cruise-produced Mission: Impossible. First, that he’d lead it. Second, that because the lead of Mission: Impossible is Jim Phelps, so surely Cruise would be Phelps.

Hmm, though. Phelps was a pre-existing character whose actor had portrayed him for nine seasons of TV and stepping into someone else’s well-established role is hardly Tom’s speed. Moreover, Phelps wasn’t a young character - Peter Graves, when he signed off the role in 1989, was 64. If the movie was going to be a continuation of the show (and in the event, it was), then there’s no way Cruise could be a 64-year-old dude. If there’s one thing Tom Cruise abhors, other than antidepressants, it’s seeming old. In 2017’s The Mummy, he is described as a “young man”.

So, no to Cruise as Phelps. In the event, they cast age-appropriate Jon Voight, now most famous for being a weird right-wing crank on Twitter, and Cruise found an elegant solution to the lead-problem: he simply created a new self-insert hero character and made him the centre of the entire story.

Ethan Hunt was born. His first act, like many sons, was to murder who came before him and take his place.

From here on out, pretty much, Tom Cruise picks the directors.

One might assume from his established control freakery that Tom would want pliable journeymen directors who can serve his will - a Jaume Collet-Serra or Shaun Levy type. The fun thing is, though, his tastes for Mission: Impossible were generally quite the opposite. The pattern of Mission: Impossible’s auteur era, the sequence of four movies all handled by vastly different directors, is that Cruise finds someone interesting and lets them cook - at the very least in the early going. The man has layers.

First at bat is Brian De Palma, a choice that I assume seemed somewhat odd at the time. De Palma had been working in Hollywood for nearly three decades, directing movies that I guess you could call successful. Carrie? Scarface? Blow Out? Seen them?

(I haven’t, by the way. Don’t look at me like that. You shouldn’t have expected any better of me.)

Befitting Cruise’s new big tycoon guy status, he found De Palma in an appropriately glitzy way - through their mutual buddy Steven Spielberg. Heard of him?

Spielberg, at this point, was in one of the hottest phases of his career, having directed Jurassic Park and Oscar-winning Schindler’s List in the same year just a couple of years beforehand. It wouldn’t be until the next decade/century/millennium that the two of them would work together, but when they got to it, they would cook quite nicely.

Anyhow, the Mission script zagged through the typewriters of some of Hollywood’s biggest screenwriters under De Palma’s direction. There were three credited writers on the final script, and the combined prestige of them could have killed a medieval peasant - David Koepp had co-written Jurassic Park (and would later go on to have a truly odd career including Spider-Man, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull and the Cruise The Mummy reboot that will haunt this newsletter later), Robert Towne had written Chinatown and Cruise/Tony Scott vehicle Days of Thunder, and Steve Zaillian would later write two Martin Scorsese movies.

We’ll put a pin in Mission screenwriters now, but suffice to say: some weird guys have gotten their hands on these scripts.

It should be noted that, ten years on from Top Gun, Cruise was going into the main action role of his career, one which would span three decades, in his mid-thirties. That’s not unprecedented, and nor would it be seen as an aberration - Robert Downey Jr., for instance, debuted as Iron Man aged 43. It’s also true that Ethan Hunt is a bit of a move forward from the “young hotshot” archetype that Cruise brought to Top Gun - there is a conscious acknowledgement that this is not the same guy.

Still, it’s as good an indicator as any of how intrinsic eternal youthfulness will become to Cruise’s public (and, you suspect, self) image in later years. If Ethan Hunt is the kind of role that would be a breakout for most actors in their twenties, then, well, that’s just how Tom Cruise sees himself: whatever age he really is, he believes that he’s younger.

The funny thing is, I wrote all of that before rewatching Mission: Impossible, and the thing I had forgotten was that the movie really does begin with Jim Phelps as the leading guy. The first 15 minutes - a suspenseful heist sequence that’s stylish as hell - are a condensed version of what I imagine a classic M:I episode to have been. You have the video briefing, a little team banter, and then the mission. Jim Phelps is the leader. He gets the mission. He’s the main guy.

Tom Cruise, on the other hand, is introduced as just a member of the ensemble - obviously the wisecracking cool one, who stands out among the archetypes of “snarky tech guy”, “posh British lady”, “Jim Phelps’ trophy wife” and “Hannah”, but still one amongst many. He’s what TV Tropes would call a Canon Foreigner, an original creation for the film, but he slots neatly and without fuss into the existing Mission framework headlined by Phelps. He knows his place.

Then everybody on the team fucking dies except Tom Cruise. He runs around the streets of Prague in a tuxedo, sweating, as he watches the entire cast of Mission: Impossible, including Jim Phelps, die brutally. By 25 minutes, only he remains. The lone survivor. I mean, it’s a great opening. Establishing a status quo and knocking it out from under our feet before the first act is even done? That’s De Palma magic. It is, also, a subtextual minefield, knowing what we know about Tom Cruise.

Really, it’s difficult not to read a movie in which he graduates from side character to lead and then takes over the front man role and builds his own team of supporting characters as a kind of commentary on the way Cruise insists on doing things.

It’s what I’d call Big Todd Boehly Energy. The new boss has taken over the old place, and he’s determined to not only make moves, but let you know he’s making moves. Unlike Todd Boehly, however, Cruise is good at what he does. He justifies his internal coup. From his magic tricks to his manic intensity in that sit down with Henry Czerny with the wild close-up angles, Cruise has the It factor here just as much as he did in Top Gun - only it’s a more refined variety, broader in its appeal than the simple mega-charisma of that 80s flick.

Todd Boehly is the new American owner of Chelsea football club. Sorry, reader. I forget sometimes.

So, Tom Cruise enters Mission: Impossible, usurps the lead role and then uses it as a vehicle for his own charisma. That would be quite a (ahem) mission statement, but it evidently wasn’t enough for Tom. He could kill the man Jim Phelps, but he could not so easily kill the idea. Strike him down and he could become more powerful than you can possibly imagine.

The only solution was to revive Jim Phelps in order to kill his very spirit.

I’m taking this all very seriously as a bit, but, honestly, I find it completely hilarious what Mission: Impossible does with Jim Phelps, the former face of the franchise. It turns out he’s the secret villain, a scumbag unable to cope with the world post-Cold War who sells out his teammates and kills his wife to make a quick getaway. Then Tom Cruise kills him again, this time in a helicopter explosion so no body can be recovered.

Nothing matches this level of character assassination. Nothing. This is like if Captain Kirk turned out to be a secret Klingon, or if Mulder or Scully picked up a cigarette smoking habit. This is turning the hero of the story into the unrepentant villain so we can cheer when Tom Cruise blows him up.

I appreciate that this made the original cast of Mission: Impossible, ahem, somewhat upset. It’s why Jon Voight is Phelps here and not Peter Graves, because Graves refused to play the character as conceived. Honestly, I’d be pretty steamed too in their position. The subtext that Phelps is some Cold War dinosaur who can’t match up to the whizz kid new guy is… well, it’s barely subtext. This is less a passing of the baton and more an armed baton theft.

It set a precedent, too. Tom would face many challengers in the decades to come - on occasion, he would invite them in. No matter the circumstance, he would teach you the one rule, the only rule that anyone needs to remember in this franchise: Tom Cruise always goddamn wins.

So, here lies Jim Phelps, unceremoniously buried in a roadside Fargo-type grave. Grass and weeds have grown over his grave in the decades since. He is remembered mostly by cultural nostalgics and weird obsessives like me. To most, he is trivia, a novelty. A funny story told long ago. The face of the Mission: Impossible franchise is the man who killed him. He has built an empire atop the forgotten ruins. The movies are pretty great.

Next time: The Mission franchises takes a hard left turn into Australian mania with the utterly bonkers Mission: Impossible 2, a movie in which motorcycles joust, and where Anthony Hopkins shows up to say the line and leave.

Can I just say - the title of this one is amazing!